There are not one but two vessels racing to be the first true ‘polar’ cruise ship, Crystal’s Endeavor and Scenic’s Eclipse, both presently under build and looking for a 2018 launch.

This pair could both be described as having ‘modest’ dimensions – although it should be noted nothing else is: bigger is not necessarily better when it comes to cruise vessels and smaller often equals ‘exclusive’, explains Jean-Jacques Juenet of Bureau Veritas. Therefore Endeavor comes in at around 183m while Eclipse is only around 165m.

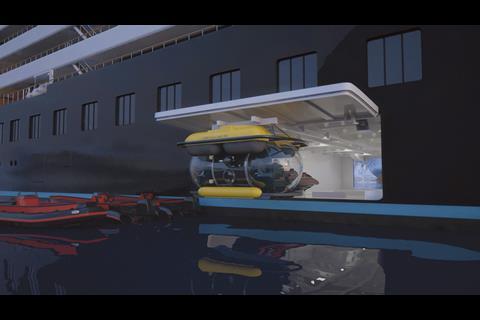

Both vessels are packing a lot in. Taking Eclipse first, not only will it have 170 crew for its 228 guests, like its bigger counterpart it will have two helicopters for ‘flightseeing’ trips, as well as RIBs and the usual luxury toys, plus an observation submarine – gantry launched from a low-level hangar – all to help the guests get closer to nature.

The 16,500dwt Scenic Eclipse, presently under build at the Uljanik Group yard in Croatia is, says Mr Juenet, “relatively compact”. However it’s still big enough to be in the ‘safe-return-to-port’ bracket he explains: these two factors pull in differing directions and have implications for the design.

“You need to duplicate the engine rooms, which is actually a little harder on this size ship than on a bigger one,” he explains. Further, he adds that beyond the necessary redundancy in safety systems and the presence of a complete ‘back-up’ bridge, there’s also an element that is particular to cruise vessels: the provision of alternative food storage and cooking facilities.

Below, two fully azimuthing, 3MW pods will give the fairly classic, 21.5m beam hull its push. As for the engines, he explains there will be four diesel generators of about 2.6MW each divided between the two engine rooms giving a total power of 10.4MW. These cover both propulsion and hotel loads – “quite generous” for a ship of this size says Mr Juenet, adding that onboard a cruise vessel the aircon and the galley are notoriously greedy consumers.

In both cases it looks like even more of a stretch as each of the vessels will be encountering an extreme range of conditions and temperatures – Eclipse’ first cruise run will take in America, Antarctica and the Mediterranean as well as the Arctic and Norwegian Fjords (for polar regions the passenger numbers will be limited to 200) and Endeavor will likewise be heading from polar regions to the tropics and back.

More, given the potential ice conditions there’s still the propulsion to take care of “and again Eclipse has that need for a safe-return-to-port with just one power line and one single pod working” says Mr Juenet.

Although Eclipse will be built to the well-known Finnish-Swedish Polar Class 6 (Ice Class 1A Super) designation, like Endeavor it is also being built in anticipation of the new Polar Code coming into force on 1 January 2017 – although this will initially cover ships built after that date a year later the code will start to apply to all ships bound for latitudes beyond the 60th parallel – this includes quite a number of more common destination ports as well as the more ‘exotic’ regions like Antarctica.

It’s a significant move as the code pushes design closer toward ‘goal-based’ solutions rather than a prescriptive set of rules – something that’s been on IMO’s cards for a while. He explains: “For example you are fairly free on the escape arrangements as long as you can demonstrate by risk analysis that they will not be blocked by ice or snow, that the lifeboat release hooks will still work in ice conditions and so on.”

The designation of Polar Code categories A, B or C depends on the operating season as well as the thickness and type of ice the vessel will encounter. Mr Juenet explains that category B means being able to encounter thin first-year ice, which may include old ice inclusions, however, he says: “This cruise ship won’t be expected to operate all year round in extreme weather conditions and won’t be designated as an icebreaker as such.”

Still he says even category B – Eclipse’ notation - needs a fair amount of consideration at the design stage.

There’s the necessary ‘ice belt’ strengthening around the waterline and there are requirements for material on the shaft line and propeller as the loads will be higher in ice conditions. Other elements are included that could be overlooked if they weren’t laid out: “There are specific arrangements for the sea chests to avoid them being blocked as even in these temperatures you need to have cooling water available,” he adds.

However, he explains these ‘goal based’ standards are not purely technical, putting greater emphasis on management aspects: IMO rules state that ships will need to carry a Polar Water Operational Manual. “So for example regarding stability we have to take into account ice accretion… the answer comes down to a mixture equipment and operation: there will be a number of heating elements but safety will also rely on regular cleaning by the crew to stop the ice or snow building up.”

For the comfort of the passengers there are also what’s being called ‘zero speed stabilisers’, fins which are actually a crossover from those found on 100m-plus yachts: “These need to work efficiently when the ship is running at very, very low or almost no speed as the passengers will want to take time watching whales or ice flows... and by proportion these are a good bit bigger – around half the size again - than the ones are usually fitted on cruise ships.”

He adds that “it’s not going to be a fast vessel by any means... the idea is to take time to explore the environment”.

This points to a rather different operational profile to that of Crystal’s Endeavor.

Endeavor is the slightly larger of the pair by some 18m. However, it’s being fitted with 22MW of power and it looks as if it will be looking at faster transits: “The usual speed for an icebreaker is 12 knots. For this vessel we are looking at more like 20 knots, so again there is a power demand, as well as high peak for ice breaking,” says Marcus Högblom of ABB Marine, the company behind the propulsion.

He goes on to point out, however, that Endeavor will also be spending a lot of time in open water. “The power demands for ice breaking are high, but you also need to be able to maximise efficiency during normal sailing,” he explains.

Given the wide operating profile, he says there are, “a lot of interesting challenges” around making best use of the power so ABB’s management system (EMMA) will allow the crew to keep track of the total energy flow around the vessel.

Both Eclipse and Endeavor have responded to the potential for abnormal loads being placed on the propellers during ice running and Mr Högblom says ABB’s XO Azipods will be modified: “These ones will be made out of stainless steel and the blade area and angle have been optimised using calculations of the ice load.” He adds that the adaptation reaches all the way into the control programming: “We also needed to take account of ice operations in the software we use to control the azipods,” he explains.

One last point: the trend toward pushing into unspoilt regions could impact the pristine wilderness that people have come to experience. Therefore both Crystal and Scenic are responding to the need for clean and green engineering to reduce the impact of carbon emissions, electricity and other resources with advanced treatment for black and grey water systems. Away from the ice, dynamic positioning will allow the vessels to hold station over interesting but sensitive areas where dropping an anchor would result in damage to coral reefs, seagrass beds and other natural beauties.

Crystal president and CEO Edie Rodriguez told press that one of the reasons for its new polar vessel is that passengers are showing a taste for “life-changing adventures” but it has to be said that these ‘adventures’ are proposed with a good margin of comfort and the best chefs money can buy.

By Stevie Knight