Once considered a “hard-to-abate” sector, shipping has begun shedding that label in favour of one more forward-looking: front-runner. And few voices capture this transformation better than Prof Lynn Loo, CEO of the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation (GCMD).

Loo starts by addressing the issue everyone concerned with future fuels considers, the supply and demand dynamic. “Pricing and supply availability are certainly challenges,” Loo begins, “but really, we’re talking about a new use case here.”

Ammonia has been safely produced and used for decades—primarily in fertilizer and agriculture—but repurposing it for maritime propulsion introduces a host of new complexities. At the heart of the issue is a fragmented supply chain and a lack of critical infrastructure.

“Green ammonia comes from green hydrogen,” she explains, “and the assumption a few years ago was that we could get green hydrogen at under $2 per kilogram. Today, it’s closer to $7 or $8.” That steep cost makes green ammonia uncompetitive, creating a barrier for both production and investment.

Compounding the problem, demand hasn’t yet materialised. “There’s neither supply nor demand right now,” Loo says. “It’s not even a chicken-and-egg problem—we don’t have the chicken or the egg.”

On the hardware side, progress is inching forward. Engine makers like MAN Energy Solutions and WinGD are in the advanced stages of testing two-stroke ammonia engines, with commercial availability expected by 2026. However, the first large vessels capable of using them won’t hit the water until Q1 or Q2 of that year.

Meanwhile, only a handful of small-scale ammonia-powered vessels currently exist—such as the Sakigake tugboat in Japan and demonstration projects such as the NH3 Kraken in the U.S and Fortescue’s Green Pioneer in Singapore. These remain exceptions rather than the rule.

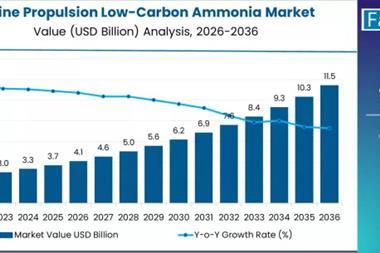

“If ammonia is to be the next marine fuel,” Loo warns, “we’re looking at scaling demand from 200 million tons of production today to as much as 700 million tons annually by 2050, with 300 million dedicated to marine use.” That dramatic increase requires an equally massive expansion of terminal and bunkering infrastructure—an undertaking that will take years.

Beyond physical infrastructure, there’s the question of operational protocols. “With LNG, we developed guidelines after operations began,” Loo notes. “Now, we’re trying to do it the other way around—establish guidelines first to guide operations.”

This inversion of traditional regulatory processes stems from the need for caution due to ammonia’s toxic nature ammonia’s toxic nature. “We need to get it right the first time,” Loo insists. “We don’t have the luxury of waiting years.”

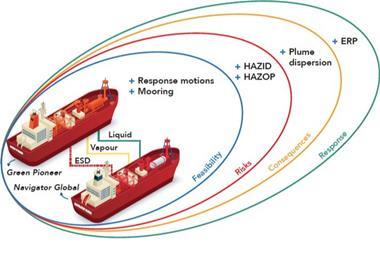

GCMD is currently focused on pilot that will generate real-world data to inform safety guidelines and bunkering standards. These pilots are being developed in close collaboration with classification societies like DNV, which are also rolling out crew training and technical assessments to support safe adoption.

A key challenge, Loo says, is the heterogeneity of the shipping industry. “Container ships, bulk carriers, gas carriers, tankers—they all have different requirements. Some vessels follow fixed routes to predictable ports, others don’t know where they’re going next.”

That variability makes ammonia a promising choice for some, but not all. For instance, gas carriers transporting ammonia can more easily use it as fuel. Beyond that, Loo sees significant potential in dry bulk carriers, particularly those operating on predictable corridors—such as the iron ore route between Western Australia and Northern Asia—where green ammonia could be available at both ends.

“Those point-to-point operations offer a higher degree of fuel certainty,” she explains. “That makes them potential early candidates for ammonia adoption.”

Even as technical readiness improves, local regulatory frameworks may lag behind. Port authorities retain significant autonomy in how they treat substances like ammonia, which could complicate global roll-out efforts.

“We’re likely to see differences in how port authorities evaluate the risks and requirements of bunkering ammonia,” Loo says. “It’s another layer of complexity that we need to work through.”

Ultimately, Loo sees the transition to ammonia as a massive, coordinated effort that needs to progress on multiple fronts: production, storage, bunkering, regulations, safety training, and vessel design.

“What we’re trying to do at GCMD is help move all the pieces,” she says. “The timeline is tight. The stakes are high. But the potential for impact is enormous.”

Underwriting the risk

One of GCMD’s more forward-thinking initiatives has been its close engagement with the insurance sector. As Loo explains, “We’ve actively sought partnerships with insurance companies, because there’s no past record with ammonia propulsion.” That lack of historical data presents a unique challenge when it comes to assessing and pricing the risk of using ammonia as a marine fuel.

“Insurance companies rely on precedent. With ammonia, that precedent doesn’t exist. So this becomes a co-learning opportunity,” says Loo. Through GCMD’s pilot projects, insurers, like Gard AS whom GCMD partners with, can start shaping risk models for future low-carbon fuels. At the same time, these insurance partners provide critical advisory input and potentially even underwriting support to ensure safety and financial feasibility. It’s a symbiotic relationship—one that accelerates innovation while managing the inherent risks of venturing into uncharted territory.

The maritime sector’s relatively progressive stance on decarbonisation has surprised many. Compared to other hard-to-abate industries, shipping seems unusually aligned in its commitment to change. Loo offers a few compelling reasons why.

“Shipping is global,” she notes. “That means we have a unique opportunity to pass global regulations. You don’t get that in the power sector, which is far more fragmented and jurisdiction-dependent.” This global nature is precisely why recent moves by the International Maritime Organization (IMO)—particularly the approval of a global pricing framework—carry such historic weight.

“Shipping is essential to global trade. If we don’t decarbonise shipping, we can’t claim to have green products. Everything we own has likely touched a ship at some point in its supply chain.”

Loo highlights the recent IMO framework as a game-changer. “We’re cautiously optimistic,” she says, referring to the vote coming in October that will determine the framework’s formal adoption. “Once adopted, all of shipping will need to comply. That’s what makes this so powerful. It’s gone from laggard to leader almost overnight.”

The alternatives

When asked about alternative fuels, Loo is pragmatic rather than prescriptive. “This is not the time to pick winners and losers,” she says. “We need a portfolio of solutions. Every fuel—whether it’s fossil-based, ammonia, methanol, or nuclear—comes with its own set of trade-offs.”

Ammonia, for example, presents toxicity concerns. Methanol’s Achilles’ heel is the limited availability of green methanol. And nuclear? “I’m a huge fan of nuclear,” Loo admits, “but the regulatory and societal hurdles are substantial. Today, nuclear-powered ships exist—but they’re mostly in the military, and some as ice-breakers in the Artic, and have only called at commercial ports on rare occasions.”

For Loo, the path forward is clear: a multi-fuel future tailored to shipping’s diverse operating conditions. “Unless we drastically change how shipping works, we’re going to need multiple fuel options,” she says. “There’s no one-size-fits-all solution here.”

Crystal ball time

Looking ahead 10 to 15 years, Loo remains both realistic and hopeful. “We’re living in a geopolitically fragmented world right now. There’s growing trade uncertainty and a questioning of the rules-based order. But climate change is a shared problem. Your CO₂ is my CO₂.”

That shared accountability, she believes, offers a rare opportunity for collective action. “Decarbonisation is one of the few things that can still unite us. We need to keep our eyes on the ball, even as we grapple with issues like defense spending and energy security.”

For Loo, the real question is whether the global shipping community can rise above the noise and focus on the shared horizon. “We must work together. This is our chance.”

Lynn Loo’s vision isn’t utopian—it’s rooted in the hard realities of technology, regulation, and geopolitics. But her belief in collaboration, adaptability, and innovation underscores a growing sentiment across the sector: maritime is ready not just to follow, but to lead.

And in this race against time, that leadership couldn’t come soon enough.