As the new year dawns, a familiar debate has resurfaced, fueled by headlines in outlets like the BBC and The Times. At the heart of the controversy is the MV Glen Sannox, a new dual-fuel LNG/MGO ferry servicing the route between the Scottish mainland and the Isle of Arran.

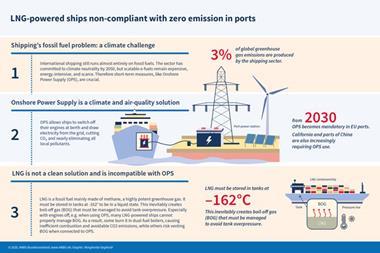

Critics have pointed out that this vessel emits more CO2 than the 31-year-old diesel-powered ship it replaced, a fact exacerbated by the contentious issue of methane slip. But this story underscores a deeper paradox within the maritime industry’s decarbonisation efforts: Are we unfairly penalising vessels that use alternative fuels like LNG while ignoring the broader environmental cost of what these ships carry?

The MV Glen Sannox was heralded as a step forward in reducing shipping emissions, but its introduction has reignited debates over LNG’s efficacy as a transition fuel. Methane slip, the release of unburned methane during combustion, significantly undermines LNG’s purported climate benefits. According to data from CalMac, once methane slip is factored in, any CO2 reductions achieved by using LNG over traditional marine diesel evaporate. This is a familiar topic for readers of The Motorship. Just last week, we featured Wärtsilä’s Juha Kytölä discussing their NextDF technology, which aims to mitigate methane slip—but solutions like these are still in their infancy and not yet industry-wide.

Complicating matters further is the issue of well-to-wake emissions. Critics of the Glen Sannox’s analysis noted that it failed to account for the emissions generated during LNG’s production and transport from Qatar to Scotland. Under the European Union’s FuelEU Maritime regulation, which takes a holistic approach to emissions accounting, such omissions would render LNG’s environmental case even less convincing. This points to a growing need for more comprehensive assessments that capture the full environmental impact of a ship’s fuel—from extraction to combustion.

A cargo conundrum

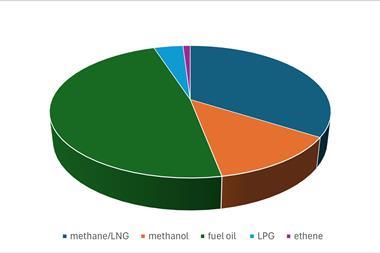

But the discussion doesn’t end with propulsion systems. The maritime industry faces a glaring contradiction: while ships are racing to decarbonise, a significant portion of their cargo remains the very fossil fuels driving climate change. Estimates suggest that over 40% of the global fleet’s cargo comprises oil, coal, or gas. This figure casts a long shadow over shipping’s decarbonisation narrative. Even if every vessel were powered by zero-emission technology tomorrow, what would these ships carry in a net-zero world?

At The Motorship’s Propulsion and Future Fuels conference in Hamburg last November, I posed this question to several industry leaders. The consensus was that, eventually, ships currently transporting fossil fuels will pivot to carrying green fuels such as ammonia, hydrogen, or methanol. But this vision remains distant. The infrastructure, technology, and market dynamics needed to support such a transition are still nascent.

The EU’s FuelEU Maritime regulation aims to drive the industry toward greener alternatives by enforcing stricter emissions standards and promoting low-carbon fuels. However, its impact may be limited by the very structure of global trade. Fossil fuels dominate as cargo because they underpin the energy systems of most economies. Until global demand for oil, coal, and gas diminishes—a monumental task in itself—shipping’s decarbonisation efforts will remain paradoxical. The cleaner the fleet, the dirtier its cargo seems by comparison.

A zero-sum game?

This paradox raises uncomfortable questions. Are we simply shifting the environmental burden rather than eliminating it? Penalising LNG-fueled ships for their methane slip, while valid, risks obscuring the larger issue: the fossil-fuel-intensive nature of global trade. This dependence on fossill fuels creates a zero-sum game where progress in one area—cleaner propulsion systems—is offset by the very cargo carried by the ships.

Moreover, the criticism of ships like the Glen Sannox could discourage further investment in transitional technologies. While LNG is far from perfect, it represents a step away from traditional marine diesel. Penalising such efforts risks sending a chilling message to an industry already grappling with razor-thin margins and enormous regulatory pressure.

What’s needed is a more balanced approach. FuelEU Maritime and similar regulations must incentivise innovation without penalising early adopters of transitional technologies. This could involve offering credits or leniency for ships that adopt LNG while simultaneously investing in methane slip mitigation. Additionally, well-to-wake analyses should become standard, ensuring that the environmental impact of fuels is assessed comprehensively.

At the same time, the shipping industry must engage with its broader role in the global energy transition. As the world moves toward net-zero targets, demand for fossil fuels will decline. Shipping must prepare for this shift by investing in the infrastructure needed to transport alternative fuels. This will require collaboration across the value chain, from fuel producers to port operators and shipbuilders.

The maritime industry stands at a crossroads. On one hand, it must decarbonise its operations to meet the targets set by the Paris Agreement and IMO. On the other, it must confront its role as a critical enabler of fossil fuel trade. Resolving this tension will require systemic change—not just cleaner ships but a cleaner global economy.

The case of the MV Glen Sannox highlights the complexities of this journey. While the ship’s LNG-fueled engines may not yet deliver the promised emissions reductions, they represent a step in the right direction. Criticising such efforts without acknowledging the broader context risks undermining the very progress we seek to achieve. As we navigate the turbulent waters of decarbonisation, the industry must remain focused on the horizon: a future where both ships and their cargo align with the goals of a sustainable world.