America’s position on lower-carbon marine fuels is not so much contradictory as revealing.

It tells you a lot about how Washington thinks power, markets and climate policy ought to work. On the one hand, the US has moved with remarkable aggression to block the International Maritime Organization’s attempt to impose a global carbon pricing mechanism on shipping.

The rhetoric has been theatrical, casting the proposal as an inflationary “global tax” that would ultimately land on American consumers. Threats of retaliation, ranging from tariffs to port fees and even visa measures, have hovered over the negotiations, turning what is usually a technocratic UN forum into something closer to a trade skirmish. The message is clear: global levies dreamed up in London and Brussels will not be allowed to dictate costs to US industry.

Yet step away from the IMO chamber and the picture looks rather different. Domestically, the US is hardly in denial about the need to decarbonise shipping. The proposed Clean Shipping Act of 2025, with some remants of its National Blueprint for Transportation Decarbonisation, would push the sector towards net zero by mid-century through fuel carbon-intensity standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Washington is also enthusiastic about alternative fuels, particularly those that can be produced at home. Biofuels, including ethanol, are politically attractive because they align climate goals with farm-state economics, even if questions about scalability and lifecycle emissions remain.

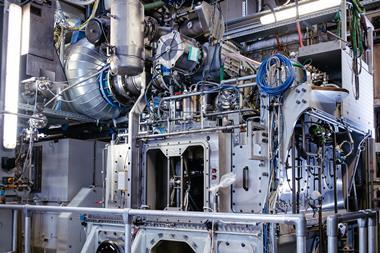

Synthetic e-fuels sit comfortably within the US narrative of technological prowess, while green hydrogen and ammonia are treated as long-term strategic bets rather than near-term fixes. American diplomats are perfectly happy to champion green shipping corridors and initiatives such as the Clydebank Declaration (albeit a signatory before Trump’s inaugration) so long as they are framed as partnerships and pilots rather than tax regimes.

What looks like incoherence is better understood as a preference for control. The US is not rejecting decarbonisation; it is rejecting the idea that decarbonisation should be enforced through a global price signal beyond its influence. Washington would rather see markets shaped at home, innovation subsidised domestically and exporters given the chance to turn climate policy into an industrial opportunity.

The irony is that parts of the US fuel industry see the IMO framework as a gift, a ready-made global market for American low-carbon fuels. But that kind of opportunity only appeals if it comes without a supranational cashier. In shipping, as elsewhere, the US wants a greener system, just not one that sends the bill from the IMO.