Nuclear energy is back in the mainstream media although not in a maritime context. US president Donald Trump has stated he is going to start testing his country’s immense nuclear weapon arsenal, something the country hasn’t done in over 30 years.

This news perhaps doesn’t bode well for proponents of using nuclear energy to power the global fleet because even though the technologies being researched for that use do not use material that can be refined to become weapons grade, it’s not great PR.

Public perception is the perhaps the biggest barrier to nuclear ships becoming a mainstay on our oceans any time soon. Aside from the unpalatable use of nuclear for creating weapons that could destroy the earth (many times over), there’s a longlist of nuclear power station disasters that span generations.

I remember Chernobyl when I was growing up, with schoolteachers telling us to shut the windows at school when winds were emanating from a certain direction (east in this case). For those just a tad older, Three Mile Island is the nuclear reactor meltdown story that causes some to shudder when thinking of the subject.

More recently, we had the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster which considering was triggered by an earthquake, how could it be safe to have a nuclear reactor powering a ship, especially in rough seas?

Given earlier special reports on future fuels highlighted issues like supply and demand problems, insufficient research and prohibitive costs with many of them, a fuel that is virtually emission free should be a no-brainer. It’s also been used in a maritime context for nearly a century, although mostly for submarines.

It’s been tried before

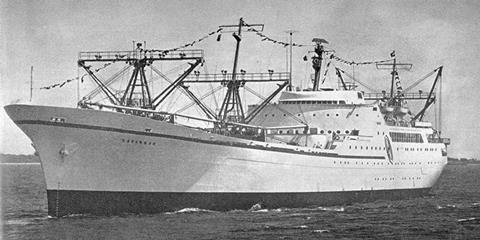

In 1953, then US president Dwight D Eisenhower delivered his “Atoms for Peace” speech, at the height of the Cold War. This wasn’t just paying lip service to pacifists fearing a nuclear Armageddon, the result was the ill-fated NS Savannah, the first nuclear-powered merchant ship. Over 70 years ago, we could have started a maritime revolution that if taken up by the entire industry could have made a tangible difference to the health of our atmosphere.

Yet Savannah’s story is rarely told outside specialist circles, and when it is, it is often framed as a cautionary tale rather than a pioneering step. The ship was conceived not only as a technical demonstrator but also as a floating ambassador for peaceful nuclear energy, intended to counterbalance the atomic anxiety of the era. Launched in 1959 and entering service in 1962, she was elegant, almost futuristic, with sweeping lines more reminiscent of a luxury liner than a cargo vessel. Her pressurised water reactor powered her reliably and safely, and by most technical measures she did exactly what she had been designed to do.

The problems that dogged Savannah were not engineering failures but economic and political realities. Her cargo capacity was deliberately limited to maintain her sleek profile, making her commercially uncompetitive. Port fees and security protocols related to her nuclear plant were onerous, and crews required extra training, which increased operational costs further. Many ports, particularly outside the United States, were reluctant to accept a nuclear vessel at all—an early sign that public perception and diplomatic caution could trump scientific reassurance. By 1971 she was taken out of service, a victim of operational inefficiency rather than any failure of her reactor. The narrative that “nuclear didn’t work” stuck, even though it was the framework around the ship, not the reactor inside her, that fell short.

This legacy still casts a long shadow. When the public hears “nuclear ship”, they do not think of Savannah or the many decades of trouble-free operation by naval reactors. They think instead of mushroom clouds, exclusion zones and dramatic television recreations. For an industry already under scrutiny for its environmental impact, attaching itself to a technology with such emotional baggage is daunting. Yet it is precisely because of that scrutiny that nuclear deserves a clear-eyed reassessment. Zero-carbon propulsion that avoids the infrastructural limitations of many alternative fuels is not something to dismiss lightly.

Modern nuclear concepts are worlds away from the large, bespoke systems of the 1950s and 60s. Small modular reactors and microreactors—many using fuels that physically cannot reach weapons-grade enrichment—offer a fundamentally different proposition. They are designed for passive safety, meaning they shut down without external input, and they can be built in factories rather than bespoke shipyards. Some concepts operate at lower pressures, others at higher temperatures with solid or molten salt fuels, but all share the aim of delivering reliable, emission-free power with minimal risk. In principle, they could provide stable propulsion for decades without refuelling, eliminating bunkering infrastructure and dramatically reducing maintenance.

But none of that matters if the public does not accept it. A container ship calling at 30 ports will only be as welcome as its reactor allows it to be. The maritime sector thrives on predictability, and the uncertainty surrounding nuclear acceptance is a commercial deterrent. Shipowners hesitate to invest in a technology that may face port restrictions, prolonged regulatory approval processes, or insurance complications driven more by perception than evidence. It is easy to see why fuels like ammonia or methanol—despite toxicity and infrastructure challenges—currently feels like a safer bet politically.